Practical Issues on the Incorporation of Partnerships

Incorporation relief

Incorporation relief, referred to in the legislation as ‘Roll-over relief on transfer of business’, under TCGA s.162 provides relief where the assets of a business are transferred to a company in exchange for shares.

Calculation of relief

TCGA 1992 s.162(4) provides the calculation for relief as follows:

It is also worth noting that, where a number of classes of shares are issued as consideration, the relief should be apportioned between each class based on their market value on a pro rata basis (TCGA 1992 s.162(3).

As is made clear from the formal name of the relief, incorporation relief is a roll-over relief with the relief calculated being deducted from the base cost of the shares received.

There is no formal claim for relief, provided the condition below are satisfied, relief is automatic.

Conditions for relief

The key elements for relief (TCGA 1992 s.162(1)) are:

- The business is transferred as a going concern

- The business is transferred wholly or partly in exchange for shares

- All assets of the business are transferred, with the possible exception of cash

S.162 is silent on the transfer of liabilities suggesting the assumption of liability by the company could be treated as non-share consideration. Consequently, HMRC have issued ESC D32, outlining that they are prepared ‘not to treat such liabilities as consideration’. The concession goes on to states that s.162 ‘is not precluded by the fact that some or all of the liabilities of the business are not taken over by the company’.

Therefore, relief may still be available whether the partners decide to transfer none, some or all of the liabilities of the business to the company. However, note example 2 below as to circumstances where the assumption of liabilities by the company may restrict the amount of relief.

This applies in circumstances where the level of share consideration cannot (under company law) cover the chargeable gain.

Whilst the first two conditions outlined above are often achievable without issue (see SDLT on incorporation of a property partnership for further analysis on a ‘business’) the final condition is not always practical.

That is to say, there may be assets that the partners wish to retain in personal ownership meaning incorporation relief will not be available. The most common example being property held on the balance sheet.

In these circumstances a claim for gift relief under TCGA 1992 s.165 may be more appropriate.

Planning opportunities

Whilst relief applies automatically if the conditions are met, planning may be possible in order to maximise tax efficiencies.

Firstly, if the circumstances are such that obtaining any relief on incorporation would not be beneficial, TCGA 1992 s.162A allows the individual to disclaim the relief.

Secondly, given incorporation relief applies whether the consideration is wholly or partly in exchange for shares, transferring the business with an element of deferred consideration (usually credited to a director's loan account) will result in an element of the consideration to remain subject to CGT.

This may be beneficial to utilise the individual’s annual exempt amount, capital losses and venture capital deferral reliefs.

Alternatively, the individual may wish to incur some CGT at rates up to 20% now in order for tax free withdrawals from the company against the directors' loan account rather than taking dividends or salary at rates up to 38.1% and 45% respectively.

Debtors

Whilst s.162 allows for cash to be retained on incorporation without affecting relief (this is logical given the cash generated from the business will have been subject to income tax in the unincorporated business) there is no such relaxation for debtors, despite the fact that the same principle applies. Once the debts have been collected in the company, there will be an issue of distributing those debts which are likely to be subject to income tax again as a distribution.

The simplest solution is, where possible, collect as many of those debts as possible prior to incorporation. However, in many cases, this is unlikely to be practical.

Another solution will be for the individuals to buy the debts from the partnership and take them into personal ownership. By doing this, the additional cash in the business can still be retained on incorporation such that a double tax charge is avoided.

It may be the case that the company will be appointed as an agent to collect the outstanding debts on behalf of the individual.

Gift relief

As an alternative to incorporation (or where incorporation relief is not available e.g. where the individual does not wish to transfer all assets of the business) gift relief under TCGA 1992 s.165 may be available.

In this case the relief must be claimed and this is achieved via a joint election between the transferee and transferor.

Whereas with incorporation relief the gain is deferred against the new shares acquired, under gift relief gain is rolled over against the base cost of the assets now owned by the company. Resulting in greater potential capital gains in the future for the company.

This leads to what could be the biggest drawback of the gift relief method, the potential double tax charge.

Whilst the company effectively inherits the base cost of the individual transferor, on a future winding up of the business, the assets would be sold by the company and subject to corporation tax on the gain. The shareholder is then likely to extract the cash under a liquidation paying CGT on the proceeds. Given the base cost of the shares is trivial the majority of the proceeds would therefore be subject to CGT in the hands of the shareholders as well.

Essentially, in these circumstances, the company pays tax on the gains using the original base cost and the shareholder pays CGT on the proceeds on extraction as well.

For this reason, where possible, incorporation relief is generally the preferred method on incorporation of a business.

Incorporating a partnership – practical examples

Example 1

A partnership with four equal equity partners acquired goodwill for £500k in March 2001, the current market value of the goodwill is £10m and the partners intend to incorporate the business by 31 March 2023.

As all the assets of the partnership are to be transferred to the new company and it will do so in exchange for 25 Ordinary £1 shares being issued to each of the equity partners, the conditions for incorporation relief under TCGA 1992 s.162 are met.

Therefore, the incorporation may continue without any tax implications.

Example 2

The facts are the same as example 1 except that the partnership has commercial debt of £2m on the balance sheet which will be novated to the company as part of the incorporation.

Again, all the assets are being transferred to the company in exchange for share capital meaning the conditions for incorporation relief are met, however, under company law it is not possible for the company to issue shares in excess of the market value of the business transferred.

The calculation of the share capital to be issued is as follows:

|

Goodwill |

10,000,000 |

|

Book debts |

(2,000,000) |

|

Share capital to be issued |

8,000,000 |

However, the capital gains tax calculation for incorporation relief purposes is as follows:

|

Goodwill |

10,000,000 |

|

Tax base cost |

(500,000) |

|

Chargeable Gain |

9,500,000 |

|

Roll over against shares |

(8,000,000) |

|

Remaining subject to CGT |

1,500,000 |

Note that the gain exceeds the available share capital to be issued and it is not possible to create a negative base cost on the shares as a result of TCGA 1992 s.169(4) which states that the relief shall not exceed the cost of the new assets.

Therefore £1,500,000 of the gain remains subject to CGT on incorporation.

Example 3

Two brothers operate a financial advisory business together. They have grown the business over the past 10 years based on their reputation and word of mouth. As such, they have a client base worth £5m and no tax base cost. The annual taxable profits for the past two years have grown significantly to £1m a year and are expected to continue to grow. Whilst each partner requires a maximum £150,000 drawings per year to fund their lifestyle. The significant income tax liability is considered unmanageable given the future growth plans of the business. Therefore, the decision to incorporate the business has been taken.

The conditions for incorporation relief (TCGA 1992 s.162) are met as:

- The business is transferred as a going concern

- All assets of the business are transferred (other than cash)

- The business is transferred wholly or partly in exchange for shares

Given the shareholders require annual drawings of £150,000 p.a. and there is excess cash on the balance sheet it is proposed to take advantage of the ‘partly in exchange for shares’ provision within s.162(1).

That is, on incorporation, the new company will issue £4m worth of share capital and deferred consideration of £1m.

The above conditions continue to be met in order to provide relief from the £4m share capital issued. However, the £1m deferred consideration will be subject to CGT in the year of incorporation.

Business Asset Disposal Relief under TCGA 1992 s.169I will not be available by virtue of TCGA 1992 s.169LA.

Therefore, the gain will be taxable at the higher CGT rate of 20% meaning a CGT liability of £200,000.

However, the remuneration strategy for the shareholders over the next 5 years will be to draw income within their basic rate bands of £50,000 p.a. The remaining £100,000 per year will be drawn against the deferred consideration created on incorporation.

SDLT on the incorporation of a property partnership

In the above examples there is no transfer of land & buildings nor stock or marketable securities, therefore, stamp duty and stamp duty land tax are not in point.

In the context of a property partnership (or indeed a trading partnership that holds land and buildings) SDLT is likely to be a significant consideration in planning for an incorporation.

Particularly in light of FA 2003 s.53 which deems the transaction to occur at market value where the purchaser is a company and the vendor is connected with the purchaser. As a result, even where the property is gifted to the company on incorporation (and gift relief claimed for CGT purposes) this will not resolve the SDLT problem.

Given the ‘higher rates’ incurred by a company on the acquisition of residential property in excess of £40k, the SDLT charge on incorporation in these circumstances can not only be significant but often deal breaker.

There are a number circumstances in which the lower ‘non-residential’ rates of SDLT apply, briefly these are:

- Where a property comprises both residential and non—residential use, the non-residential rates will apply to the entire transfer.

- Where there is a transfer of six or more separate dwellings on incorporation FA 2003 s.116(7) treats the dwellings as non-residential.

- Multiple dwellings relief may also be in point whereby the average value of the properties is used to determine the rate of SDLT, subject to a minimum rate of 1%.

Sum of lower proportions

However, in the case of partnerships there are special provisions within FA 2003 Sch 15 dealing with the transfer of property from a partnership to a ‘connected’ person, in this case the acquiring company. The result being that the provisions of FA 2003 Sch 15 Para 18 take precedence over the market value rule of s.53.

Connected

The definition of ‘connected’ for these purposes can be found at FA 2003 Sch 15 para 39 which directs us to CTA 2010 s.1122 with the important omission of s.1122(7), the partners in a partnership clause.

s.1122(3) states that a company is connected with another person (‘A’) if A (which may include their connected persons) has control of the company. Control in this case being defined by s.1124 as having the power to ensure that company’s affairs are conducted in accordance with their wishes.

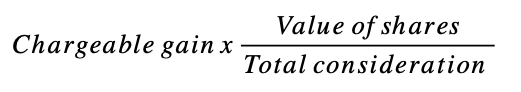

Calculation

FA 2003 Sch 15 para 18 provides the formula by which the chargeable consideration is calculated being:

![]()

FA 2003 Sch 15 para 20 provides the steps for determining the sum of lower proportions and these are also outlined in HMRC manual SDLTM33750. This can be a complex calculation and should be reviewed in detail for each transaction.

As a general rule, where the beneficial ownership of the partnership and the beneficial ownership of the shares in the company are the same, the sum of lower proportions should provide a result of 100 meaning the market value is multiplied by a factor of 0% to provide a chargeable consideration of nil.

This is not a relief to be ‘claimed’ but simply how the chargeable consideration is calculated in these circumstances.

Anti-avoidance

Given the potential for a property partnership incorporation to be completed without a charge to SDLT it would be a relatively simple step to create a partnership solely for this purpose and incorporate shortly after.

For this reason, the general anti-avoidance rule of FA 2003 s.75A may be invoked by HMRC where they consider the partnership to be for avoidance purposes. The effect of s.75A being that the creation of the partnership will be ignored by HMRC in determining the SDLT on incorporation.

Existence of a partnership

Despite the anti-avoidance rules, there may be circumstances where a partnership exists for SDLT purposes, regardless of whether a formal partnership agreement exists or partnership tax returns are submitted to HMRC.

Indeed, in SC Properties Ltd v HMRC [2022] UKFTT 214 (TC) decided in July 2022 and involving the incorporation of a property development business, the FTT considered factors such as whether contracts and invoices had been entered into in the name of the partnership (they had not, they were in the name of the ‘partners’ personally), furthermore, ‘The Partnership did not have its own bank account and was not registered for VAT’.

The FTT therefore found for HMRC and concluded that a partnership did not exist meaning SDLT was found to be due.

To determine whether a partnership does exist we must consider the Partnership Act 1890 s.2(3) which states:

The receipt by a person of a share of the profits of a business is primâ facie evidence that he is a partner in the business…

The key here, as in the case of incorporation relief for CGT purposes, is the existence of a ‘business’.

What is a business?

Despite relating to VAT, a number of cases in this area have addressed the question of what a business is for VAT purposes and therefore this provides useful guidance for the purposes of SDLT on incorporation as well.

For many years, the primary case in establishing the existence of a business was C&E Commrs v Lord Fisher [1981] STC 238. In this case the judge outlined 6 indicators in establishing whether a business exists:

- Is the activity a “serious undertaking earnestly pursued”?

- Is the activity an occupation or function actively pursued with reasonable or recognisable continuity?

- Does the activity have a certain measure of substance as measured by the quarterly or annual value of taxable supplies made?

- Is the activity conducted in a regular manner and on sound and recognised business principles?

- Is the activity predominantly concerned with the making of taxable supplies to consumers for a consideration?

- Are taxable supplies that are being made of a kind which, subject to differences of detail, are commonly made by those who seek to profit from them?

Whilst there is no formal change in law, from 1 June 2022 HMRC guidance (see Revenue and Customs Brief 10/2022) proposes 2 new cases to consider for the purposes of determining whether a business exists:

- Wakefield College v CRC [2018] STC 1170.

- Longridge on the Thames v HMRC [2016] EWCA Civ 930.

Following these, more recent, cases the following tests have been outlined:Does the activity result in goods or services being supplied for consideration?

As part of this test, there must be a legal relationship between the supplier and recipient.

It is quite clear that there must be a ‘supply for consideration’ and the judgement by the Court of Appeal in the Wakefield College case made it clear that this is a necessary factor in assessing the existence of a business activity but that it does not, in and of itself, provide the sole test.

Is the remuneration earned from the activity obtained for the purpose of receiving income?

The first test has already outlined that the supply must be for consideration, this further test then takes this a step further requiring income to be generated from the activity.

Of course, charging a consideration may mean a nominal consideration simply to ensure the creation of a legally binding document, e.g. in the case of acquiring an insolvent company, £1 is still paid to make the contract legal. Therefore, the value of the consideration must be sufficient to show an intention to generate income and not, in most cases, be lower than the cost of supply the goods or services.

Furthermore, there is a distinction here from an intention to generate profit. As HMRC outline in their manual VBNB30300 ‘An intention to make a profit is a strong indicator that the activities are intended to generate an income but the reverse is not necessarily true.’

VBNB30300 goes on to outline two further indicators of income being:

- Is the activity conducted based on sound business principles?

- What is the scale of the activity?

- In relation to property partnerships, this is an important factor to consider. Owning a single rental property that a husband and wife wish to incorporate is unlikely to constitute sufficient activity, whereas a number of properties where the partners are involved actively in managing the properties is much more likely to constitute sufficient activity as indication a business.

That being said, a key case in the context of incorporation relief (as outlined in HMRC manual CG65715) is Elizabeth Moyne Ramsay v HMRC [2013] UKUT 0226 (TCC), where, on the incorporation a single apartment block, sufficient activity was involved to constitute a business.

Originally, the FTT had found the activities of Mrs Ramsey were normal and incidental to the owning of an investment property. However, the UTT decided that the FTT has made an error in law and it reversed their the decision.

The key points of the case were:

- The ‘business’ consisted of a joint interest in a single apartment block divided into ten self-contained flats.

- The property consisted of a communal area, a garden, car park and garages.

- Mrs Ramsey was personally involved in carrying out substantial repair and maintenance on the property.

- Mrs Ramsey was also involved in carrying out preliminary work for the planned refurbishment and redevelopment of the property prior to the incorporation.

- Mrs Ramsey and her husband each spent 20 hours a week on the management of the property business and neither of them had any other source of income during the relevant period.

A crucial question in the case of partnership incorporation is, therefore, are the activities sufficient to constitute a business and not merely incidental to owning an investment property?

In CG65715, HMRC state that, for incorporation relief purposes:

You should accept that incorporation relief will be available where an individual spends 20 hours or more a week personally undertaking the sort of activities that are indicative of a business. Other cases should be considered carefully.

Further proving that, whilst the number of properties may be a useful indicator, it is certainly not decisive.

Issues arising on the cessation of partnerships

LLPs and tax transparency

For tax purposes an LLP is generally treated as transparent and the individual partners are therefore subject to income tax on the annual profits of the partnership.

For CGT purposes, this rule is outlined in TCGA 1992 s.59A(1) which requires the LLP to carry on a trade or business with a view to profit.

Therefore, following incorporation, the LLP’s business is likely to cease along with the tax transparency.

Whilst s.59A(3) allows the tax transparency to continue in the event of a ‘temporary’ cessation, s.59A(3)(b) also allows the transparency to continue during a period of winding up provided tax avoidance is not a motive of the winding up and the winding up period is not unreasonably prolonged.

In most circumstances this should not be an issue, but it is important to be aware that the LLP should be wound up as soon as practical following the incorporation.

Failure to do so will result on chargeable gains of the LLP being computed as if the LLP had never been tax transparent.

It is also worth noting that, on incorporation, unlike normal partnerships, company law requires the issue of new shares to be made to the LLP itself and not the individual partners. This means that the LLP must be wound up in order to distribute the shares of the company to the individual partners.

Whilst, in practice, a number of transactions have been completed issuing shares directly to the individual partners, this tends to be in the case of family businesses not involving third parties.

Closing year rules

The partnership will cease and the closing year rules will apply

In the tax year, the profits arising in the period from the day after the previous basis period ended to the date of cessation are taxed.

Simply put, on the cessation of trade, any remaining profits are taxed, making sure that there are no gaps or overlaps in the profits that are being taxed.

Transfer of plant & machinery

On cessation of trade, the P&M is deemed to be disposed of which will create balancing adjustments.

If P&M is sold to the company for consideration, the disposal value to use in the partnership tax return is the lower of actual consideration received and original cost.

Where P&M is transferred to the company for no consideration, the disposal value to use in the partnership tax return will be the lower of market value at the date of transfer and the original cost.

The disposal of the P&M to the company will give rise to balancing allowances (if disposal value is less than tax written down value (‘TWDV’)) or balancing charge (if disposal value is more than TWDV)

CAA 2001 S.266 election (succession election)

Where P&M is transferred between connected parties, a joint election may be made (in writing to HMRC within 2 years of transfer date).

The effect of the election is to transfer the P&M at TWDV instead of market value to avoid balancing charges & allowances

N.B. No AIA is available on the acquisition of P&M from a connected party.

Transfer of stock

Stock will have to be transferred at market value due to the connection between transferee and transferor meaning a profit is likely to be realised in the final partnership accounts.

ITTOIA 2005 s.178 (Stock election)

In order to resolve this, it is possible to elect to transfer stock at the higher of:

- Original cost

- Actual price charged

Nick Wright

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

07891 203889