Selling out of an employee ownership trust

Published in Taxation on 28th February 2023, written by Pete Miller and Nick Wright.

A great deal has been written about selling companies into employee ownership trusts (EOT).

Now that the legislation is nearly nine years old (it was enacted by FA2014), some of the early adopters are finding that companies are being sold out of the EOTs. We have recently been involved in such a transaction which threw up some interesting issues, so we thought we would share our experiences.

The tax rules

For those readers who are not familiar with the legislation, a sale of shares of a trading company into an EOT will be free of capital gains tax (CGT), as the transaction will be treated as a no gain, no loss transaction for capital gains purposes, so long as a number of 'relief requirements' are satisfied (TCGA 1992, s 236H). The relevant legislation is at TCGA 1992, s 236H to s 236U.

Very briefly, the relief requirements are:

- The trading requirement is that the company must be a trading company or the principal member of a trading group (TCGA 1992, s 2361), meaning a company or group that 'carries on trading activities and whose activities do not include to a substantial extent activities other than trading activities'. This definition will be familiar to anyone who has looked at capital gains gift relief, business asset disposal relief (BADR) or the substantial shareholding exemption.

- The all-employee benefit requirement (TCGA 1992, s 236J) broadly requires that the trustees can only apply the property of the trust for the benefit of eligible employees and to do so in line with the equality requirement (TCGA 1992, s 236K), which allows benefits to employees to be varied only by reference to their levels of remuneration, their seniority and their general hours worked.

- The controlling interest requirement (TCGA 1992, s 236M) simply requires the trust to hold more than half of the ordinary share capital of the company, to have the majority of voting power and to be entitled to more than 50% of the profits available distribution to equity holders and of the assets available for distribution to equity holders on a winding up.

- The limited participation requirement (TCGA 1992, s 236N) says that the ratio of shareholders that are employees or office holders to the total number of employees (the participator fraction) must be less than 2/5, both in the year up to the sale into the trust and afterwards.

Providing the relief requirements are met, relief is due for all sales of shares into the EOT in the tax year in which the trust acquires the 51% interest in the company.

However, a disqualifying event occurs if the company ceases to satisfy any of the relief requirements. If this happens in the tax year following that in which the relevant disposals were made (ie those disposals for which a claim for relief would be valid), no relief is due to the vendor shareholders under these rules (TCGA 1992, s 2360), and any relief already given must be withdrawn. If a disqualifying event happens at any later time, the trustees are treated as having sold the shares of the company immediately prior to the disqualifying event, and as having immediately reacquired them (TCGA 1992, s 236P). Given that the base cost for the trustees will, in many cases, be no more than the nominal value, this could give rise to a significant capital gain.

It is therefore generally vital to ensure that there is never a disqualifying event, so that the trustees do not suffer a 'dry' tax charge. However, while a sale of the company by the trustees is clearly a disqualifying event, since there is an actual disposal, not a deemed disposal, there should be cash available to fund any payments of capital gains tax.

Legal and commercial background

We will assume for the purposes of this article that the trust held 80% of the shares of the company and the husband-and-wife team that founded the company still held 10% each. While this article is not intended to cover the consequences of the sale by those individuals, we note that they would be entitled to make their own decision as to whether they wish to accept the offer, unless there are drag-along clauses in a shareholders' agreement that would require them to sell if the trustees decided to sell the shares, in which case their options might be more limited.

More importantly, those shareholders may be entitled to claim BADR on the current disposal. Regardless of the actual proceeds of the sale of 80% of their shares to the EOT, this was deemed to be a no gain and no loss transaction, so that sale will not have had any impact on their eligibility for BADR. In our case, the wife was a director of the company but the husband was not employed, so he did not qualify for BADR.

In contrast, the trustees must consider, primarily, the interests of the beneficiaries, being, broadly, the employees of the company. So, the trustees must decide to sell based on whether doing so is in the best interests of the company's employees. The decision will usually be based on how much will be available to distribute to the beneficiaries (see below), rather than any personal considerations.

The trustees consisted of three individuals including the original director shareholder. Given her position as a trustee, vendor shareholder, director and married to the other shareholder, there was a potential conflict of interest. It is always important in these cases for the trustees to be able to demonstrate that they are genuinely acting in the best interests of the beneficiaries and not also considering their own personal positions. In our case, there were two other trustees, one being a member of the company's employee council and the other being independent, so we had no qualms about the independence of the trustees' decision to sell.

As an aside, we did not see any real potential for conflict in advising all of the vendors in the transaction, although we were aware that conflicts could have arisen. We raised the possibility at the beginning of our work, so that had a conflict arisen we would have been able to discuss it sensibly with our clients.

Capital gains tax

A major element that the trustees have to bear in mind is the CGT. As a discretionary trust, it is assumed that CGT will be payable at 20% (TCGA 1992, s 1H(8)). As in many cases involving a sale to an EOT, the original base cost to the vendor shareholders is very low and the trustees have inherited that base cost, as the disposal into the EOTs was a no gain, no loss transaction. On that basis, as can be seen from the example, we have assumed that that there is virtually no base cost, so the trustees will pay CGT at 20% on pretty much the whole of the proceeds.

Sums available for distribution to beneficiaries

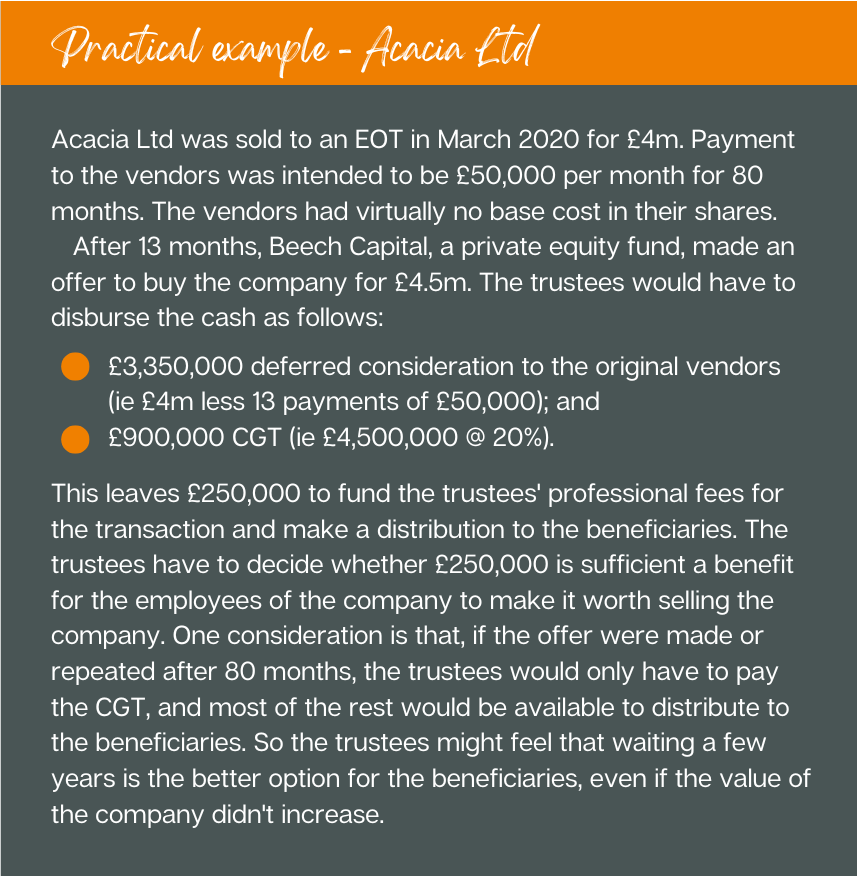

In general, people decide whether to sell shares on the basis of price and the post-tax return. So they will look at whether now is a good time to sell or whether a better price might be expected if the shares were sold a few years later. This will obviously also influence the trustees, but more from the perspective of how much will eventually be available to distribute to the beneficiaries, after paying any sums still due to the original vendors. So, for example, the trustees might consider it better to hold on to the shares until they have been paid for. Even if the company were to be sold at the same price some years later, if the debt owed by the trustees has been discharged, there will clearly be more funds available for the beneficiaries, so a later sale at the same price might still be best (see Practical example -Acacia Ltd).

It is clear from the above that the factors that the trustees must take into account will often be very different from the matters that affect the minority shareholders, as can also be seen in the example.

Who are the beneficiaries?

To qualify for relief when the shares were originally sold into the EOT, the arrangements had to satisfy the all-employee benefit requirement, as outlined above. The beneficiaries are all of the employees of the company, except for the vendor shareholders, any other person who holds 5% or more of the company's share capital or of any class of the company's share capital, and anybody connected with them (TCGA 1992, s 236J(3), (5), (6)). In our relatively simple case, the only two people excluded from benefit were the vendor shareholders.

One would assume, therefore, that, if somebody ceased to be employed by the company, that person would no longer be a beneficiary of the trust. However, where the trust ceases to hold any of the company's share capital, the beneficiaries are taken to include both current employees and those employees who have been eligible employees at any time within the two years prior to the disposal (TCGA 1992, s 236J(4)). In some cases, with a relatively small workforce, the number of leavers in the previous two years might be relatively low, so this would not present any practical difficulties. However, in our recent case, the business involved a lot of hourly-paid employees, which implies an extremely fluid workforce. This meant that there were a lot of people who had left the employ of the company in the two years prior to the sale.

Furthermore, given the menial nature of the work and the type of employee concerned, tracking them down could be a real problem in many cases. This has nothing to do with tax per se, although the issue arises because of the tax rules, so our advice to the client was that they would have to take advice from their lawyers as to what provision they would need to make, and for how long, in respect of ex-employees who were theoretically beneficiaries of the trust under these rules but could not be traced.

The lesson learned in this case is that clients should be advised when they sell shares into an EQT that they may need to trace ex-employees if there is ever a sale from the EQT, so they should keep appropriate contemporaneous records.

In our particular case, the problem was exacerbated by virtue of the fact that the consideration for the purchase of shares would be partly deferred. This meant that the final tranches of consideration, which would include the amounts that would become distributable to the beneficiaries, would not be paid for up to 12 months after the completion of the transaction. This made no difference to the CGT position for the vendors, as deferred consideration left outstanding is simply brought into the capital gains computation in the year of completion (TCGA 1992, s 48(1)). But it does create a further practical requirement to keep track of anyone who was a beneficiary by virtue of being an employee at the time of the sale, but who might leave that employment before the full consideration for the transaction had been paid.

Once again, this is largely a matter of trust law, and not a tax issue. But we were aware that the purchasers were keen to lock employees into the company, and that they wanted to make distributions from the trust conditional upon people remaining employed for the year until the final consideration was paid. Our concern was that, if somebody was entitled to benefit from the trust surplus by virtue of having been an employee at the date of completion, it might not be lawful for the trustees (or anyone else) to impose further conditions on the rights of those individuals to benefit from the trust's surplus.

Taxation of distributions to beneficiaries

As we understand it, the distribution of surplus funds to the beneficiaries is treated as earnings, on the basis of the decision in Brumby v Milner 51 TC 583. This was a case where a trust for the benefit of employees was wound up and the proceeds were distributed to those employees. The High Court, the Court of Appeal and the House of Lords all found that the payments were made to the employees because they were employees, so that all the sums paid to the employees on the winding up of the trust were earnings.

This means that the distributions are chargeable to income tax on earnings as well creating a requirement to account for National Insurance contributions, both by the employer and the employees. In effect, what this says is that, while the employees might benefit from an increase in value of the company while it is owned by the trust, they will be taxed on those proceeds as if they were earnings. Furthermore, the amount available to distribute to the beneficiaries will have been reduced by the capital gains tax charge on the trustees, which smacks of double taxation.

Operation of PAYE/NICs

The big question is about who should operate PAYE. On one level, it seems logical that trust should be treated as the employer for these purposes, as it is the trustees that are paying the surpluses to the beneficiaries. However, this would mean that the trustees would be required to set up a payroll system and register it with HMRC, before operating PAYE and accounting for NIC on the distributions, and then winding up the payroll scheme before, presumably, winding up the trust, itself.

A further issue that arises here is that the trustees may well not have the pay and tax details for the beneficiaries, which means that they may have to deduct basic rate income tax, so that many of the beneficiaries will end up having overpaid tax and would have to complete tax returns for the relevant period in order to claim back any overpayments. We assume that HMRC does not really want to increase the income tax self-assessment burden in this way.

Many of these issues could be easily resolved if the actual employing company were to operate PAYE. This could be done by having the employing company operate PAYE on behalf of the trustees, in which case the trustees would contribute the relevant amounts of tax and NICs to the company, to pay to HMRC, and the trustees would distribute the net amounts to each of the relevant benefits series. Alternatively, and perhaps the simplest solution, is for the trustees to contribute the entire surplus to the company on the basis that the company will then pay that out as earnings to each of the relevant benefits series. In either case, one assumes that the employing company will have the pay and tax details of most of the beneficiaries, apart from those that are not currently employed by the company. Plus, of course, they will already have a payroll scheme set up.

One possible downside to either version of this solution is rooted in the fact that the trustees are only entitled to apply the trust property for the benefit of the beneficiaries. It has been suggested that the liability to account for employer's NICs is a liability of the employer, which means that, strictly, contributing to the employer's NICs bill of the company would be ultra vires use. While we understand the point that has been raised, it seems to us that the employer's NICs are inextricably bound up with the payment of earnings to the beneficiaries of the trust, so it would be unlikely that anyone would seriously argue that paying employer's NICs was somehow ultra vires.

Conclusion

Overall, it was certainly an interesting project to be involved in and, with so few sales out of EOTs on which to draw conclusions from, the drafting of TCGA 1992, Part 7 became critical, as well as wider legislation, eg regarding the operation of PAYE.

Despite the various challenges, ultimately, we were comfortable with the general tax principles that we were trying to achieve according to the legislation as written, and therefore the most challenging aspects centred around the practical operation of the tax code. Collaborating closely with solicitors to achieve a commercially acceptable outcome alongside the trust law aspects was also crucial.

The project, however, highlighted that there are clearly a number of uncertainties presented by the legislation that would benefit from some clarity in order to reduce any doubt and simplify the process for future transactions.

Furthermore, there is much incentive for the vendor shareholders in selling into an EOT but the drawbacks of a sale by an EOT seem to contradict the idea of genuine employee 'ownership'. If the intention is indeed for employees to have a share of ownership, why are the proceeds subject to tax as earnings? Why is there a double tax charge with the trust being subject to capital gains tax on its proceeds on top of the employee tax charge.

We expect there will be many cases where an EOT is approached by a buyer where the trustees, acting in their role as in the best interest of the beneficiaries, will reject genuinely reasonable offers, regardless of potential benefits this may present for the trade because, once the CGT charge has been paid, remaining deferred consideration paid off and PAYE and National Insurance operated on the earnings, the proceeds for the beneficiaries will simply not make the transaction viable.

Nick Wright

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

07891 203889

Published in Taxation on 28th February 2023, written by Pete Miller and Nick Wright.

https://www.taxation.co.uk/articles/selling-out-of-an-employee-ownership-trust